Growing up in a Waco, Texas, during the 1940s, avant-gardist Robert Wilson—a pillar of the experimental art world and founder of the Watermill Center—had never met an artist. "When I was 12 years old, I met Clementine Hunter and bought a painting of hers," Wilson said. "Her work has always inspired me. For our 20th anniversary gala I thought to honor her."

In celebration of the Watermill Center summer benefit's two decades of history on Saturday night, Wilson staged an homage to Hunter, bringing to life the self-taught African American folk artist's body of work—but in a very Watermill way. True to his word ("We always try to do what no one else is doing."), Wilson transformed a Hunter canvas of red and white angels flying over a field of green into this year's theme: "Devil's Heaven."

"For me, 'Devil's Heaven' is about two worlds being one," Wilson said. "Heaven and hell exist together."

Major figures from entertainment (Lady Gaga, Hugh Jackman, Winona Ryder), fashion (Bill Cunningham, Nicole Miller, Rick Owens), and art (Cindy Sherman, Marina Abramovic, Kyle DeWoody) indulged together in Watermill's devilish paradise among some 1,200 cocktail guests, 700 of whom stayed for the seated dinner. Actor Alan Cumming manned the spotlight as M.C., although Lady Gaga controlled the buzz with her surprise attendance, bleached eyebrows, and $80,000 acquisition of two works by Dieter Meier and Abramovic. Swiss auctioneer Simon de Pury hosted the pre-dance-party live auction, which helped to raise $1.85 million for the center's ongoing residency and education programs.

Setting a heavenly scene, the white dinner tent and tables created a canvas for streaks of colorful cloth runners, each dotted with miniature reproductions of Hunter canvases. A four-sided installation at the center of the tent recreated certain works, including "Cotton Pickin'" and "Arc en Ciel"—Angels and Rainbow, adorned with 3-D elements like arms and wings. For dinner, Canard served a "devil's garden" salad made, fittingly, with baby heads of lettuce, followed by a roasted hen stuffed with summer fruits and brioche. Bacardi, Mouton Rothschild, and Peroni provided the bar.

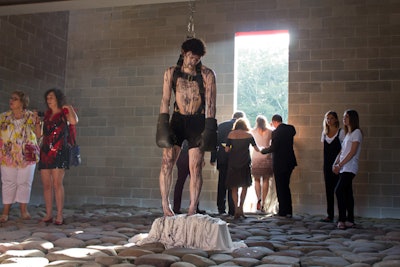

Outside the tent, a fiendish spectacle ran wild. Arriving guests were greeted by Trina Merry's installation of two performers perched on a pedestal, their naked bodies painted green and flowering with magnolia branches. That proved to be only the first of many nude works by Merry, including an enchanted forest of performers painted to look like bark and pressing their nymph-like flesh against trees. Merry's "Objectified" conversely presented painted bodies as man-made items, like chairs, lamps, and ironing boards. Then there was Lisa Lozano's "Funérailles de Miel," in which patrons were encouraged to spoon honey out of a box where a female performer lay nude, half-submerged in sticky sweetness.

At the center of it all was a recreation of Hunter's African House, a wide-roofed structure on the Louisiana plantation where Hunter worked, which featured prominently in her autobiographical art. "She is someone who never learned to read or write, but she has documented life through pictures," Wilson said. "Many of my early works were silent and told stories through pictures, so I feel close to Clementine Hunter's work."

Looking back on 20 years of Watermill's annual Hamptons fund-raiser, Wilson judged Saturday evening's success by the swell in attendance since 1994. "At the first benefit, Donna Karan chaired; we had 120 people," he said. "This past Saturday we had 1,200." One of those people, asked in passing how this year's benefit compared to the year prior, put it more succinctly: "Well, it isn't raining."