Early in his remarks at the Moth Ball, host Garrison Keillor told the guests that he had recently suffered a stroke. The room fell quiet. He went on to say that his was a mild stroke, “the best kind to have.” Then he admitted that telling New Yorkers about it had a surprise benefit. “In the world of New York City conversationalists, it’s like having a handicapped parking permit.” Rather than being interrupted within 10 seconds, as is our city’s norm, he said, leading with the stroke news gave him a “fighting chance” to last, say, “20 to 30 seconds.”

It was his way of congratulating the 12-year-old organization on its surprising success in the city that “doesn’t sleep and certainly doesn’t listen.” The Moth is a not-for-profit group that holds story “slams” for anyone with a story to tell, now also in three other cities (Los Angeles, Chicago, and Detroit). People line up around the corner, sometimes waiting for an hour to pay and listen to (mostly) amateur storytellers. Hundreds of people at dozens and dozens of events, each with a different one-word theme—who knew?

Well I guess I kind of knew; I’d seen their mailings for years, always intrigued, but afraid my Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder made me ineligible to attend. But when I heard their annual Moth Ball, held November 17 at Capitale, would feature not only Keillor—Mr. Lake Wobegon himself—but also a black and white masked ball, I mustered the courage.

What a hoot! This is obviously a very hip and cool crowd, numbering 600 guests. The committee had interesting (for a change) celebrities (Rachel Weisz, Darren Aronofsky, John Turturro), literary types (Malcolm Gladwell, Adam Gopnik, Gay and Nan Talese), and stylistas (Lucy Sykes Rellie and her hubby, Euan, Simon Doonan and his mate, Jonathan Adler, who designed the handsome awards), and everyone donned their best downtown finery to preen.

I have written here before about what makes a good masked ball. I’ll skip all the rules but one: Provide masks for the sticks-in-the-mud who are too lazy (me) or forgetful (also me) to bring one. Here, in addition to the dime-store variety, the Moth team handed out swish, frilly numbers. Mine, feathered black and white in a skunk pattern with gold-sequined eyes, sits looking at me now, daring me to pretend I didn’t have fun.

My favorite was a pair of girls, Sarah and Jarema, who work as art assistants for an art duo named Faile, and who were apparently artistic themselves, with one-eyed numbers, à la Phantom, with what looked like owl feathers and scarabs. Others took the mask cue one step further and went for partial costumes. One beaver top hat (from SoHo’s the Hat Shop) would have done Dr. Seuss proud. An otherwise very conservative looking older fellow opted for a black feather boa with gilt trim. Finally, there was Light Man, whose neckpiece featured a programmed diode light box that broadcast all sorts of nifty shapes and patterns.

Masks make people chatty, and isn’t that what makes a party? I first met Tully McGregor, who explained to me what the Moth story slams are all about. First you go to themoth.org and check the schedule for a theme that appeals to you, preferably I guess in your neighborhood. Then you show up early and pay $7 (it just went up from $6) and put your name in the hat if you want to go on stage and tell your story. Thus, the Moth’s motto is “A Story, a Microphone, and You.”

Tully, who is featured in the organization’s identity video by Ogilvy Public Relations that debuted that night, also kindly explained the rules. When your name is called from the hat, you have six minutes to tell your story. You get a warning at five minutes and the rug gets pulled at six. No notes. You tell your story from your head. The story must feature you and be nonfiction (hard to enforce this point, I think). It must directly address the theme of the night (war, vegetables, almost anything really). No props. Then the judges (there are lots of them) score you with cards like at a diving meet, and there’s a winner. Then there are Moth grand slams and all sorts of other events, all culminating in this, the Moth Ball.

Tully turned me on to Adam Wade, the most successful storyteller in the Moth’s history, who has won 15 Moth story slams, and begins every tale with “Hi, I’m Adam Wade and I’m from New Hampshire.” Moth by night, by day Adam does TV production and is a budding writer (Glamour, The New York Times) with a literary agent. But he said he doesn’t do Moth story slams for the fame or recognition (and I believe him, but just in case, go to adamwade.com); he just loves it, which everybody at this party says.

So tonight, because of the gala format and all, they have roped in famous storytellers Mr. Keillor and Jonathan Ames and Anna Deavere Smith (she gets the handsome trophy aforementioned). But to keep it real—and the Moth it seems is all about keeping it very real—in addition to fancy arty types, many of the storytellers are homeless, or recovering (hopefully) drug addicts. I met Julia Wayne, who was performed a one-minute story entitled “Love in the Time of Heroin.”

She is being “story coached” by the Moth senior producer Jennifer Hixson, who came to tell a story one night 10 years ago, stayed on as a volunteer, and now helps run the outfit. She’s an attractive, lively sort, and clearly a good storyteller herself. She explained that the organization has education and therapeutic benefits and outreach of all kinds. The Moth even does corporate counseling, telling companies like Dunkin’ Donuts, Nike, and Maybelline how to tell their stories. Again, who knew?

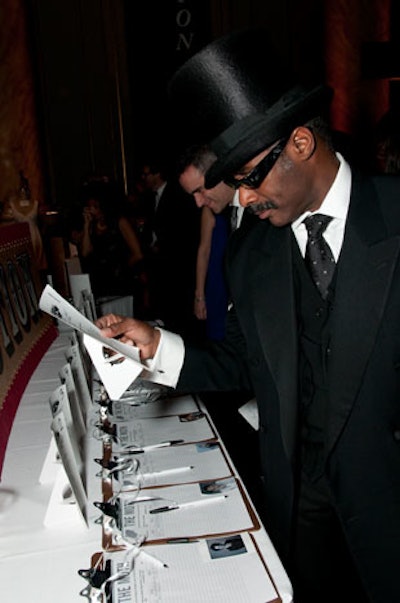

Jennifer had to go get her storytellers in line, so I checked out the auction items, many of which showcased the unique literary/talky-talk nature of the group. You can have lunch with Salman Rushdie or buy Garrison Keillor’s loaded Kindle. I bid on a three-night stay at Casa Genotta in Sea Island, Georgia, where I grew up going and didn’t even know that the casa in question used to belong to Eugene O’Neill. While signing up, I met a lady writer who knows my Uncle Tim from Sea Island. It was that kind of night.

By which I mean to say the best kind of night: entertainment that tells and sells the cause’s story at the same time. Elements of party fun and frivolity tempered with just enough seriousness to justify them. And a cast of characters you want to see again.