David Adler (@DavidAdler) is the C.E.O. and founder of BizBash.

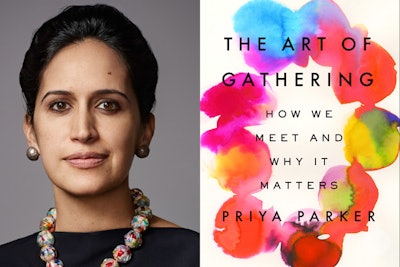

The first time I talked to Priya Parker we clicked. In her new book, The Art of Gathering, she says that smart event organizing, in all its forms, is a powerful tool that has been underrated and minimalized—feelings that I share.

Parker describes the Japanese tea master concept of “ichigo ichie” as it relates to events. The great tea masters of Japan believed that “if you step into the same spot of a river, a week from now the river has changed, but so have you.”

From an event perspective, the term means "one time, one meeting" and describes a cultural concept of treasuring meetings with people and can also mean "for this time only," "never again," or "one chance in a lifetime." The phrase reminds people to cherish any gathering that they may take part in, since many meetings in life are not repeated. Even when the same group of people reconvenes, a particular gathering will never be replicated; thus, each moment is always once in a lifetime.

Parker, like the Japanese tea masters, believes that even if you gather the same people at a similar place, the event is totally different because we are changed and we are different. She states that an event is a temporary alternative world that takes design elements from gaming and shares her idea that there is a magic circle that you go in an out of to be part of the event.

Many of us focus on the logistics and the accoutrements, which in today’s world need to be flawless or else we shouldn’t be in the business. The emphasis now needs to be on the purpose of live gatherings to justify the time that it takes, not only to produce, but to show respect for the guests at our events.

In the 100th episode of GatherGeeks podcast, Parker talked about her book with BizBash editor in chief Beth Kormanik and me. You can listen to the episode here or read the transcript, printed below, for insights into what I think is the future of our industry.

Beth Kormanik: Your book just came out and you know, the title almost makes it sound like it's a coffee table book, but really it is very much a practical guide for people, and I'm wondering when and how did you get the idea for this book?

Priya Parker: So the subtitle is how we meet and why it matters, and I got the idea of the book in part because I was frustrated by going to a variety of different events, where you know, whether it's a dinner party and the table was beautiful and the food was spectacular and people left feeling a little bit sort of hollow and empty and not connected to each other. Or conferences where you know, perhaps the speakers were great, but again, people who were actually at the conference didn't connect or feel inspired by each other and kept basically asking why is this, and from my perspective, a lot of the gathering was demand guidance that we've turned to over the last few decades and have been outsourced primarily to people who are kind of experts in food and recipes and flowers, even etiquette. Not that those aren't part of a gathering, but to have that disproportion of focus on it, is a missed opportunity to actually focus on people. I wanted to write a book that didn't focus on the things of gathering but rather the people, and coffee table books and partners are attractive because things are visual, whereas the interaction and meaning between people is much harder to describe unless you were there.

BK: You're coming at this from a different perspective. At Thrive Labs you are working on corporate and nonprofit gathering strategies, but more than that as well. Your bio says you've worked on race relations on college campuses, peace in the Middle East. So there's a lot of conflict resolution. So what do these things have in common, and how did that shape your perspective working on this?

PP: I come to this primarily as a conflict resolution facilitator. So my craft, my profession, is in group conflict resolution. I worked first in my career as a college student and then as a graduate on race relations on college campuses in a process called sustained dialogue. It was founded by a former diplomat Harold Saunders, and he was the crafter [and] one of the co-creators of the Camp David Accords, you know, peace between Egypt and Israel. And he was obsessed with the interaction of people in a group, sort of the technology of group relations, and he was my mentor. So ... the reason I was in the Middle East for different dialogues was because at 70 and 80 years old, he was always curious about, and supported, young people. I came into this world through conflict resolution that looked at, how does a group transform its relationship? Not between two people. So not marriage counseling or business partner counseling but the dynamics and the messiness of group life. I wrote this book to help people think more like a facilitator.

David Adler: You actually broaden what event organizing is about by this approach, and have you seen any results in terms of how people react to this—they say, oh, wow, this is right?

PP: I—absolutely, and I think you know part of helping people see things fresh is changing the language that we use, and for better for worse, you know, perhaps I don't know 30 or 40 years ago if we used event organizing people might think, wow, what does that—but now it's an entire field and an industry, and unfortunately, we have, you know, certain archetypes that goes with what we think an event organizer is or does.

[PULLQUOTE]

DA: Yeah, we have a four letter word for that, it’s—”party planner.” Facilitators are using the new methodology of what I call, being a “collaboration artist.” When I saw the article on you in The New York Times the other day I said, oh my God, this is exactly what we're about.

PP: Absolutely. The core DNA of event planning to me is the radical engagement of people for a temporary moment in time. I think that the best people in this field and outside of the field think about, how can I create a magical memorable experience for a group of people that will move them in some way? Unfortunately, in part because when you're working with a client or in a corporate context, depending on when you're being brought in, the you know, the train is already kind of moving and you have to focus and very quickly get kind of stuck into the logistics roll. To me the most important thing to start with a gathering even when you're brought in at the third step or you know, once everything is moving, is to pause and say, what is the purpose of this gathering? In part, many times when we don't ask that purpose we quickly get to the form of what we think something should look like and it actually doesn't match the need of the people.

DA: How do you get people to understand the concept of purpose? So what is the methodology to get someone to say, what is the purpose of my event and how can I really make it more strategic?

PP: The first thing is actually to pause our mindsets in our frameworks, about our assumptions of a purpose of an event. So I say that first, because asking the purpose of something is a very easy thing to do [but] we don't do it because we think it's obvious. So the first thing I'd say is no matter what, ask the purpose of the event. So for example, if somebody says, you know, we want to have an "ideas festival," ask why. If we want to have a 50th anniversary or a 70th celebration of the founding of our company ask why, ask what for, ask who is this for?

I write about a gathering in the book that, I don't name the company, but it was a 250th celebration of a company, and I was invited as a guest, unfortunately for the company, and it was this, you know, multimillion-dollar rollout of events all over the world, and when the one in New York happened in Lincoln Center, and it was sort of spectacular in terms of the fireworks and there were movement artists going through the space, and the food was sort of delicate and perfect, and they had the waiters come out in beautiful style, but the entire thing had no logic and no story and didn't connect people, and the entire audience, they're dressed in black tie.

I believed that at the end of the night the audience felt quite used. And even for that I think part of the reasons we skip the question about purpose is because if you hear, oh, it's a 250th anniversary celebration we think we know what that is for, but is it to honor the founders? Is it to honor the future? Is it to honor the vision? Is it to honor the specific product? Is it to bring together a company? Is it to find new clients? Is it designed to increase your followership on Instagram? Your purpose can be crass, but you should know what it is.

DA: How do you uncover the real purpose of an event?

PP: The first thing you continue to say is "what is this for?" They'll probably look at you and laugh. And so the second thing is to ask the question again. What is this for? For example, right now a lot of companies want to get into the conference business. It's a trend more and more people realize that's a way to kind of build a brand and get new clients.

So if we're working with somebody and they say we want to have a conference, the first thing is literally just to ask why, and they say because it's kind of what everybody's doing. All the media companies are doing it. I want to have a conference. Okay, so but why do you want to have a conference? What is the need that you're trying to solve for? ‘Um, I don't really know if we have a need.’ Then don't plan a conference. Right? So part of this is guiding people to figure out what is the right format for an event when a gathering doesn't fulfill a need. It's very difficult to make it matter.

BK: Is the purpose different from the message?

PP: Yes. So the purpose might be totally invisible, you may never tell anybody what the purpose is and may just be felt through the design of the gathering, whereas a message might be the name, or the tagline, or the hashtag of a conference or of a gala. The purpose is really the animating force of why you're doing what you're doing, why you're bringing people together. One way is to kind of zoom in so people want to have a conference get them to actually focus on what it is they want to have a conference for. And you know conferences with kind of vague themes when they invite everybody is rarely a good conference. And so I encourage my clients to always be extremely explicit and specific to have a conference that's disputable, to have a purpose that's disputable.

So for example, ... MIT Media Lab a few years ago hosted a conference, and I think it was something called "Illegal and Unethical Research." It was a fascinating conference because even by hosting the conference researchers had to decide if they wanted to be seen there. Can we show up and does it mean that we are for this issue? It was memorable and interesting, and it kind of, and people disagree about whether or not you should even have this. That's an interesting purpose.

DA: What happens if you’re provocative in the marketing of it, but you're not delivering the expectation from the hype?

PP: I see that in a lot of brands. This isn't a gathering but the biggest example that sticks with me is the United Airlines ad from maybe 10 years ago. People, all of the staff of the United Airlines, are sitting in a meeting room waiting waiting, and you see the clock ticking—15 minutes, 20 minutes, 40 minutes, and then at 59 minutes the C.E.O. walks in and he says, and everyone's angry, and he says, welcome to how it feels right now to ride United Airlines.

As a marketing campaign, it was awesome, right? Everybody got really excited. Like wow, they realized that they're creating these terrible experiences on airlines. They're going to change it. But the problem was they didn't change the experience that embodies the message of the marketing, and so people got even more angry. I think of an air flight as a gathering.

If I was advising an airline company, every time people get into your plane, it's an experience. They enter, there's an opening, they walk in. There's a physical experience. Some people are talking to strangers and having the most beautiful conversations of their lives. So now that everyone's on their tech, there's an exit, and similarly with a conference or with any type of event planning, if the marketing is provocative and then you walk in and it's not embodied it's actually a breaking of the social contract.

BK: So you can put this event framework around so many things that we don't even think of as events. You identify a lot of almost barriers to entry like in terms of people not holding events because they are frightened of them or scare them away. Can you tell us what some of those are?

PP: Absolutely. I think that in part because, for 30 or 40 years we've been part of the eye called the Martha Stewart School of Gathering, it's become very intimidating to gather, and this is particularly true in kind of our personal lives and our social lives that you have to have the right kind of canapes and crudites. You're naked to the world at events and that will always be true. Right, so you're naked to the world. But you have to also know how to cook and you have to know how to set a table and then the, you know, more traditional you had to know the right etiquette, and I think in part because you are naked to the world. We've focused our anxieties on the things of gathering, we focus on our anxieties, on getting the perfect stew, rather than figuring out what are we going to do with the people in our midst once they're actually in the living room. I wrote this book in part because I really believe everybody can gather.

It's like, one of my favorite movies is Ratatouille. Everyone can cook and everyone can gather. The events industry is one of the most powerful and important fields in the world. When people come together possibilities are imagined, conflict can be resolved.

For this book I interviewed over 100 gatherers, including a rabbi, interviewed a camp counselor of a Jewish Arab summer camp, a Japanese tea ceremony master, dominatrix, photographers, advisors to multi-generation family businesses. One of the things that I found as I spoke to them and others is the best gatherers also suffer from social anxiety. The reasons their gatherings are excellent is because they have the empathy and understand what people feel at the extreme when they come into an environment where they have to interact with others. Usually people who suffer from social anxiety are incredibly astute and know how to add the right amount of structure that makes people feel more comfortable.

DA: Do you feel that as you do more gatherings, does social anxiety lessen?

PP: I think it lessens over time, but at least for me it, you know, it's taken many, many, many, many years to not sort of shake before a gathering. And I also think that you know, I'm a professional facilitator, my core work is creating conversations, complicated conversations between leaders at kind of transition points in their company. I've, you know, I've done this for over 15 years, and I still feel kind of sick, you know, the two to three hours before a gathering. When I don't, I get a little worried, because we care.

DA: Well also the funny thing is, I always say people that just to hold your hand out and say hello, my name is David Adler provokes such social anxiety. You actually have to push yourself to do it. One of the things you say is, “Ask not what your country can do for your gathering but what your gathering can do for your country.” What did you mean by that?

PP: I think that gatherings that start to think about how do you actually touch on or begin to approach social ails are underrepresented in the things that we think we can actually do. And this could be in a humble way. So for example, in a neighborhood that's quickly gentrifying and all of the restaurants are kind of corporate-owned, you zoom it down and zoom in, what does this neighborhood need? And you may think, I'm a chef and what this neighborhood needs more than anything is a raw granular community. So, my gift is cooking, and the way I know how to do that is to start a family-owned restaurant and figure out how to meet rents that match an Applebee's or a Chipotle, and then specifically in the way that they would start the restaurant to actively design your table so that everybody is sitting together.

One of my favorite people that I researched in this book is a man named Theodore Zeldin. I think he's now in his 80s. He's an English philosopher and for many of his birthdays through the 70s he would invite the entire United Kingdom for a birthday party in, I think it was Regent's Park. Don't quote me on that. And he would call it a feast of strangers and hundreds of people would show up and there'd be you know, tables on the grass rather than food.

It's totally free. I mean, you have to figure out how to get the tables rather than food. There'd be a menu of conversations and for every entrée every course, there'd be questions. So the fish course would be something like what's your relationship to money? Or what have you rebelled against in the past? And what are you rebelling against now? And they pair up strangers across from each other, and for every "course," they'd answer these kind of very high-risk, provocative questions. What if you in your neighborhood decided that the thing that this neighborhood needed was stitching together, you know, maybe it's a racially diverse neighborhood. Maybe it's a politically diverse neighborhood. What if you did a conversational menu? As the menu in your restaurant, that becomes interesting.

BK: So you mentioned one common thing that you see people doing wrong, and it's having an event without knowing why they're having the event. What's another thing you've identified that's going wrong, or that needs to change in terms of bringing people together?

PP: Yeah, you know and I'll just say one thing is I bristle at the idea that there's like a wrong way and a right way to do a gathering. What I'm really trying to shift is the mindset of how we approach what this thing is.

I mean, so to answer your question, I think another thing that we misunderstand is when to include and when to exclude, and I think we over-include. In a spirit of trying to be generous, I think we misunderstand the idea of the more the merrier.

So I think that the more is usually the scarier or the harrier in part because we tend to invite people out of either obligation or shoulds, or habit rather than thinking about who actually needs to be there. And so for example, I was facilitating a global worldwide meeting for a company. They had just hired a new C.E.O., and the C.E.O. was trying to find—I won't say which gender—their new feet. It was the first time the C.E.O. was kind of coming out to the entire global company, and at the last minute, they got a casual email from the founder who just wanted to stop by and be part of the proceedings, and that C.E.O.’s instinct was to say yes, because it's very awkward to say no, and I said the founder is absolutely not allowed to be here.

If they agreed to have him it would have shifted the power dynamics at a time where they're trying to talk about, and break away from, the past. It would send a very complicated message. If you're a good host you act with the spirit of generosity and you include each person, but you have to handle the dynamic. And so whoever you bring in, one, do it with purpose. But to exclude with purpose, and so in that case, we explicitly had to say, hey, you have a lot of power in this organization, you symbolize a lot of stuff that's bigger than you and we actually need to do this gathering without you. To the founder’s credit, they understood, they got it, but we're often not willing to have the complicated conversations, in part, because we have a queasy feeling. It doesn't feel like that person should be here, be there, but we don't really know why, and then even if we know why it can be complicated or awkward to say no.

DA: So one of the chapters that you have is don't be a chill host. Now, what does that mean?

PP: So I think that chillness and this kind of idea that you know, everyone should just chillax and kind of look like they don't care might be helpful when you're at home watching Netflix. I am deeply encouraging you to Netflix and chill, but when it comes to gatherings this attitude is a very dangerous idea. A gathering is a form of power, and it's a form of love, and being chill is both abdicating your power and it's also not taking care of people.

DA: So we had our conference in Florida yesterday, two days ago, and one of the things I do as a host is I go to every single table, and I welcome people and thank people. I love that, and I have seen it at the State Department when the prime minister of England David Cameron goes to every single table.I believe that many C.E.O.s are now terrible hosts. How do you tell them that it's not about them, it's about their guests? So when I read this about the chill C.E.O. it seems terrible. How do we change that?

PP: I agree totally. You know, one of the people I interviewed for the book, one of two chapters that got cut at the last minute, was on the power of the physical aspects of an event. My character is an Olympic hockey coach named Ralph Krueger. And, he recently became in a very unusual position, the chairman of a football league in the UK Southampton and one of the traditions that he was delighted to discover was that every morning when the team gathers for breakfast, the team, the assistant coach, the coach, everybody involved, before they go to get their buffet, their food, everybody shakes hands with everybody else in the room, and so if you're the first one there, you're fine. If [you’re] the second there it takes a few minutes, you know if you're the 36th person there it takes a lot longer, but it's this kind of way they’re hosting each other and they're connecting with each other, and it's a ritual, but it's something that transforms the breakfast every day.

DA: I believe that we need to bring back the receiving line, and it is because when millennials walk into a room, sometimes they never even meet anyone, they never talk to anyone. So as an organizer, I'm sure we both believe the same thing that you have to sort of tell people, you have to actually orchestrate.

PP: Completely, and I love the idea of the receiving line but we need to refresh the receiving line for the new generation.

BK: I think not being a chill host is about respecting everybody's time as well and saying, I care that you're spending your time with us. And therefore I'm going to make sure that the day is structured. You're not going to see me relaxing because it’s my job to make sure that we're spending our time effectively together.

PP: Yeah, and I think language is really important. So I think once you're actually in the room as a host, you should relax in terms of your comportment and put down all of the things that you're doing, put down your logistics, put down your phone and just be present and relax and breathe and be there.

So I have a chapter called basically “pop-up rules are the new etiquette,” and it looks at how we can design temporary rules for any gathering that are fun and playful that quickly shift the dynamic. One of my favorites comes from experienced designer, named Anthony Rocco. He has a fascinating personal story.

His father was an FBI agent and and he grew up in the Mormon church. And so he grew up both with ritual and shadow, and he's now one of the most talented experienced designers I've met. He used to be a practice facilitator for an underground secret society. That was extremely controversial and has since imploded.

It was a secret society that tried to get funding to scale. So it was just talked about. He created this rule that when people walked in they wanted to have everybody meet but not have it feel cheesy, and the rule that he set was you can't pour yourself your own drink.

So what does that do, if you think about it? It makes you pour other people’s drinks and makes them pour you a drink. And it immediately flips the dynamic so that you're caring for others and that you actually have to ask somebody to pour your drink. And so I think to me, that's kind of the modern version, a very fresh innovative way of what a receiving line used to do.

DA: You talk about when we talk about engaging, the big buzzword everywhere is, engagement, engagement, engagement, and you have these experienced designers who are creating these things that they think people are engaging in. Is marketing getting it wrong because they're creating these great you know, eye candy, but is it really working?

PP: I think if you kind of step back and think about how the economy has and will continue to change, Joseph Pines’ The Experience Economy was the first person to frame it in a helpful way, moving products to services to experiences. We're now in the thick of experiences. You can see that millennials want experiences over products and services, you know, they kind of, they named it, they called it, and in a sense the Anthony Rocco story is an example that I don't think you need to have crazy fireworks and a million-dollar budget to create a magical experience for people. You can be extremely creative to help people engage in something interesting and very simply. Certain props and things can help depending on the purpose of the gathering. I just read this in The New York Times, one of my favorite examples was the last Star Wars movie three or four years ago, the invitations came out and said in one of the small details that instead of just saying that there will be parking, they said, parking for your land cruisers will be provided and your space jets, and it was an over-the-top premiere with all these costumes and crazy props, but in the tiniest detail of the invitation, they embodied the spirit of why people are coming and so in that case, I think it makes sense to have this kind of incredibly marketed, alternative world created of a Star Wars theme, but I don't think that that should be our model for every gathering. To me event planning is not a bag of tricks, it is a lens and the lens that asks, what does this group of people need now?

DA: You say that temporary moment. You talk about how important that moment is?

PP: Yeah. Absolutely. It doesn't happen. So one of the people I interviewed, I mentioned, is a Japanese tea master, and there's a phrase I guess in the mastery of tea ceremony, which is a specific craft with the specific lineage and it's “ichigo ichie” and it means basically that, “this moment will never happen again in this way.” I was in Kyoto and did a tea ceremony with this master. It was a female master and she said, the idea is that even if you step into the same spot of a river, a week from now the river has changed, but so have you. And it's the same idea with a gathering, which is you can even do the same thing every week. The power of ritual, it's not that you actually have to reinvent every time, it can actually be very beautiful to have rhythmic repetitive gatherings that because we are changed and we are different, maybe something happened to me in the last week, or maybe my parent died or maybe I had a bad fight at work and I'm bringing in different part of myself because of that.

The second thing I'll just say is I write about this idea of creating a temporary alternative world, and I learned a lot in this book from talking to game designers, people who create games for a living, and in the game designing world, there's this idea of a magic circle.

So it comes from a Dutch game designer almost a century ago, and it was popularized by Katie Salen and Eric Zimmerman and their amazing book called Rules of Play. It's sort of like the cannon. It's literally a door stopper. ... How do you actually design rules to get people to play games? And it's a fascinating read, and I interviewed Eric for this book and one of the things that they popularized is this idea of a magic circle, and ideas basically when you decide to play a game. So like let's play tag or let's play Bluff or let's play, you know BS, I'm clearly I'm right having a lot of lying card games. The first thing that you know a group of three or more people do is say, okay, what rules do you play by, right? And say, okay the soccer ball, the tree is the post and the grass is the line and everyone kind of agrees and then we say start, and from that moment everybody imagines this temporary alternative world that we agree to that we're stepping into and we behave differently for a specific moment of time. The game then becomes over and sometimes you may say okay, pause, pause, pause. I have a question. So then they step out of that magic circle and when you say, I thought you said we were playing that you could pick up the entire card of death card not just the top. Okay. Got it. Okay. Time back in.

So you're literally jumping in and out of this make-believe space, and I believe every gathering operates the same way.

DA: It's not unlike in the book, Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind, where the whole world is some sort of artificial construct.

BK: Tell us tell us more about how you think events are like that. What are we all agreeing to when we show up?

PP: So I'll give you a specific example, so recently I had a conversation with the writer Jancee Dunn. She's an amazing writer and she was talking to me about how can she make her dinner parties kind of more engaging, and I said, well, what do you need right now? Or what are you experiencing in your life? And she said, well recently, I was with a friend and I was hungry and she cut me a peanut butter and jelly sandwich into triangles and cut off the crusts, and it amused me, and I felt really special, long story short. She decided she realized that what she needed was a gathering where she wanted to feel taken care of and wanted to take care of other moms.

So I told her to give it a name, tell the story in the email, and invite them to come, and create one rule. So the rules she created was if you talk about your kids you have to take a shot and she invited them to the Worn-out Moms Hootenanny, and she says she writes in the piece, I've never had all six of my friends R.S.V.P. yes within an hour. They're so excited to kind of step into this world. And so what I mean by temporary alternative world is these are people who see each other in a lot of different contexts. But Jancee had an idea that she as a host decided to create a specific world, and when you create a specific world you’re asking people to activate one part of their identity. All the people on that mailing list also have jobs, also play sports or have hobbies, but mother is one part of their identity. And so the first thing she's inviting them into and they can say no is tonight. I want you to show up as the worn-out mom part of yourself. So the world she's creating is activating that part of that identity primarily.

It's not that other things don't kind of triple underneath, and then the second thing is it's temporary because it's three hours. First of all, you don't have to go, right, if you don't like this idea, just say no, I'm busy. But if you say yes, you're implying that you're saying yes to a social contract. Yes. I will enter into this world. Yes, I will play with you. And then the second thing is with any type of temporary alternative world, you want to think about, where's the physical line? Where are they stepping into it? So in her case, her house, it was like the doorway. In the case of a picnic, it could be once you step onto the blanket. Allow people a physical threshold, think about their physical journey into a space and how do they pass into like from the world that they left and into the world that they came into? So one of the things I gave her as an example was when these women walk in, to dig into their purse and pull out a strange item like dried out raisins or a packs of mushed-up pears or even a straight bottle cap. And so I said, have them look through their purse and take out that one item because everybody has one, even if it's just the fact that it's a mess, and put it down in a basket and walk in and there's a symbol that they're leaving this part of their mom part out, and they were going to walk in and be part of another world for a little bit, and they didn't have to worry about their kids.

DA: So you're talking about the design of an event via the storytelling aspect. You would think that would be normal about an event. Is event design and experiential design important?

PP: Oh, it's extraordinarily important. What I'm saying is it's not, I wouldn't say it's about the storytelling, storytelling is a component of it. It's about the design of your event should match the purpose of your gathering, and the food and the drink are part of the matching of the purpose.

So in this case, I told her do not cook, do not spend three days cooking, and do not have anyone else cook. Order takeout and say that you're ordering takeout in the email because it embodies the idea that you're worn out. Right? So all I'm not ignoring the food I'm saying how about serve your purpose and spend time thinking about that purpose. Martha Stewart has a 29-point party planning guide, and you read it, and at least I feel exhausted by it. Three out of the 29 steps have to do with people and even that is logistical, check in or R.S.V.P.s, you know, send ours, make your list, and one of the steps is literally something like one day before blanche your vegetables for the crudités and keep them in separate Ziplock bags and put them in your vegetable drawer.

I'm like exhausted just reading that, and it's not, and I don't mean to pick on Martha Stewart, but the point is the emphasis has been completely distorted so that we have an assumption that this alternative world is only created by canapes or a special fizzy drink.

BK: So why do they look so appealing though? What do we respond to when we see that though?

PP: I think we respond to the idea of being taken care of, of delighting in being part of an alternative world, in the idea of escape and all of those things are beautiful, so I'm not saying don't do them. I love canapes. I really do. I love beautiful drinks, I'm a total foodie, all I'm saying is that the archetype of gatherings and of hosting, unfortunately in the American context, has come from a very specific 1950s to 1970s image of a woman in an apron holding a tray of martinis, and I think it's problematic because gathering as a form of power and a gathering as a form of love and that image excludes a lot of people, and it's not and it should be a choice. I mean, I'm very happy to wear an apron and hold a plate of martinis, but I want that to be one of a thousand images we have when we say that we're gathering.

DA: What are your favorite gatherings that you've been to recently?

PP: So one gathering that I recently went to was a baby shower, and I think in part because I think most women kind of have baby showers, but we all slightly dread them. Because there's this rope that goes along with them, and so do I really want to you know, pin the diaper on the baby and all of these things that we feel like we ought to do but again don't match the purpose of you know, why are we having a baby shower? We’re having it because we're scared of labor, we’re having it to honor the identity of a mother, we’re having it because we are celebrating the transition of couplehood actually expanding to a family, and so I went to the baby shower where the setup was that everybody kind of milled around for a while, and it was men and women and every woman was asked to bring a poem or a song or write a letter to the mother or the child and we went around and basically did that, but before each of us didn't know each other, each of us shared a story of how we knew the woman, and it was very simple and it was very beautiful because as people started to speak from the heart and share some element of why they love that person we all learned something more about a different angle of the mother-to-be, but we also became a kind of a collective hive of exchanging meaning and preparing a woman as she thinks about this new identity. And it didn't get lost in the games that have to me become more about farm than function.

DA: We do a lot of Jeffersonian-style dinner parties and we're doing them for business, and it is amazing how it's not just for your dinner party anymore, but it really bonds this, you know, new group that get together. And so what do you, what is your sort of sense of the Jeffersonian dinner party and are there other formats that kind of work?

PP: Yeah. I love the Jeffersonian dinner party, and I interviewed Jen McCrea for the book, she and Jeff Walker are like fantastic designers of experiences and hosts for experiences and I, you know, I think more and more in particularly with the kind of rising generation of millennials we're no longer saying meaning is for home, not for the workplace, and that's controversial in and of itself. There are some people that say, I don't want to share my entire life story with my colleagues, like work is work and home is home, and so that's an interesting position, like it's a juicy conversation and we should be having it.

I personally think that other people and teams work better together over the long run when they see more sides of each other and they connect, and so one of the models that I write about in the book and I love is also a structured model. It's called "15 Toasts" and it's something that I developed with a colleague of mine, Tim Labrecque. We were both members of the Global Agenda Council on new models of leadership at the World Economic Forum. We were there for meetings in Abu Dhabi, so not to boast but another meeting, and one of the things we noticed was that in all of these meetings as we kind of go and there's amazing people in the room, but everybody is in this habit of kind of the elevator pitch or the stump speech of like "oh, yeah, just like my series b" or "this is so great in my life, my life is fabulous," and "I was just in Rome," and all these things, and you can mirror it, right? That's the kind of danger of it. You kind of become yourself, someone you loathe.

BK: It's not very vulnerable. It's the opposite of vulnerable.

PP: And so we created this dinner, we thought we could hack the World Economic Forum in this small little way and invited 15 people from 15 different councils so that we kind of spread the love, and we designed this format with my husband, who was there also, and he was part of the brainstorming, and we chose a theme and invited people to dinner and felt more like a wedding or a dinner party than a conference. Lights, flowers, candles all that and the theme we chose was a good life, but you can choose any theme, and we said what is a good life to you? And at some point in the night you have to stand up, bring your glass old-school style, and give a toast.

The toast needs to be a story or an experience from some part of your life, some room you've been in that we haven't been in that relates to the theme, and the only rule is that the last person has to sing their toast, and we did it. It was beautiful and halfway through the night that was very interesting was people started talking about death and the inverse of life is death.

And what was interesting was as we started talking about a good life people started thinking about the darker sides that rarely come out in a context like this and people were crying, not only when they were giving a toast, but because they were so moved and something changed in the room that night that realized, like we are complicated people that are all playing roles and roles are good, but we're all wearing masks and sometimes those masks serve us and sometimes they prevent us from actually talking about the things that matter.

BK: Has this experience changed how you behave as a guest?

PP: It's an awesome question. I'm a little complicated because I'm a professional facilitator and my friends know that, and so when I'm a guest I'm like I try to stay hands off in part because I want to honor my friends and they kind of know that I have a very strong opinion about how things should go. But that said, I wrote this book. I purposely called it The Art of Gathering, not The Art of Hosting, and that's because I believe guests are completely powerful and transformative in any gathering. Any time I go to a gathering, particularly when I am a guest, and it feels appropriate and people aren't connecting, I will often suggest a question for the table, and if people don't want to, it's fine.

But I think guests, you know, this is a very dramatic example, but I use it because I think it's very powerful, which is when James Foley was captured by ISIS. He was in captivity for a couple of years along with you know, six to twelve other foreigners. They were obviously treated horrendously, tortured, all of that, and when he was beheaded, I read his obituary in The New York Times and there's a small detail that among everything else deeply moved me, and it was a detail that said that he among all of the captives, of all the people who were captured, they would spend their day in this room, and he was the one that would always help them figure out what game to play and find ways to entertain each other, and find everything from having them teach each other a skill to telling stories, to … playing little games with each other. There was a small detail that he grew up in a family that played a lot of games and this radical example reminded me a little bit of Viktor Frankl’s book, Man's Search for Meaning. It reminded me of that book because I thought, here is somebody with the worst hosts in the world: ISIS. And he demonstrated to me the transformative power of being a guest.

DA: Before we go. I want to know, did someone sing their toast at the end and did people put their hand up because they didn't want to be the one to sing?

PP: There's almost always like the underground singers, or it's funny, I've done it in India before and everybody wants to sing change the rule, so I changed in that case my 15 toast. I changed it so that the person, the first person volunteered and then they got to choose the next person across the table. So you kind of distribute power in a different way, but we've done like over 20 of these dinners all over the world, in Shanghai in South Africa in Copenhagen and San Francisco and Vancouver and New York, and the best themes are the darker themes.

So rebellion death, fear, scared of the dark, and people always sing. It's Chatham House Rules, so you can talk about the experience in the stories, but you can't attribute it to a person, so I'm not breaking any rules here. So one dinner the final person everybody invited had something to do with fear. It was one person was an emergency room doctor, one person was a hostage negotiator, everybody who kind of dealt with that in some way or the other, and the last person that gave a toast was an emergency room doctor, and he had a young kid, three-year-old, and he said he sang “Let It Go.” You know anyone who has children you all know the words and then all of the parents in the room, you know joined in. I've had people sing like the actual toast and have had a Finnish guy sing his toast and what was so delightful was he had a terrible voice and it was totally off-key and everyone was like very moved because you're showing yourself naked.

DA: Just simple ones that we used for our Jeffersonian style dinners are "What was your first job?" or "Who is your favorite teacher and why?" and the through line goes all the way to today and you see the power of these stories.

PP: And particularly questions that talk about anything that happened to them before they were 20. That just opens up the world.

BK: Well, your example of giving the final person in the room a special task gets to one of the points in your book. I would love for you to briefly share your philosophy on things like how to open and how to close an event.

PP: Studies show that openings and closings as a peak experience disproportionately matter, they are the things people remember, and so the opening moments and the closing moments are moments where an audience is primed to have kind of higher amounts of attention.

And because we are trying to kind of get the housekeeping out of the way. We so often start with logistics. So you are at an enormous gala, everybody's there, they're excited, and the first thing someone does is they thank the sponsors or you. I was at a funeral, this is a true story, and the minister got up there and we were all primed with emotion and very sad and grateful to be together and he said, now before we start I just want to let you know that, if you can keep your car in the parking lot here and just walk over together, there's not enough parking in the rec center. The reason I pick it out is because we don't think about it, but it affects the experience. And so I always say either find a way to communicate the logistics separately or do it second, and similarly with closings, don't end on logistics. Do them second-to-last. End on purpose.

Listen to more podcasts with event industry professionals at bizbash.com/gathergeeks.